Increasing Beneficial

Insect Populations by Increasing Biodiversity in Organic Agricultural Systems

An ant, CAN, move

a rubber tree plant

If you’ve ever been to a fruit

orchard, eaten fresh fruit or vegetables from a local stand or farmers market

it is likely that you have seen the effects of herbivory (the act of feeding on

plants) on market produce. This may present in the form of minor cosmetic

damage or as a wiggly bit of a worm staring at you from the apple you just bit

into. While these conditions are problematic they do not demonstrate the full

effect of the problem. Pest damage, including herbivory, is the second highest

cause of infield decrease in yield for market produce (fruits and vegetables)

and the leading cause of loss of yield for cereal grains, as well as being the

cause of the majority of “marketable” defects in fresh market produce(fruits

and vegetables meant to be eaten fresh) (1).

In conventional agricultural

systems pesticides have been the primary tool producers have used to control

pests. However, these pesticides, along with synthetic fertilizers are agricultural

inputs which are causing massive damage to the natural ecosystem and in the

case of pesticides can even be dangerous to human health (2). Among ecologists,

agricultural researchers and other interested parties (read: all of humanity) this

problem of sustainably controlling pests from an ecological perspective while

still achieving sustainable economic productivity should be of paramount

concern (2). Simplified, how do we feed the world without destroying the ecosystem

that keeps us all alive in the process? A possible solution comes in the form

sustainable organic agricultural systems.

The USDA National Organic Program,

the regulatory body for products labeled “Organic”, has a fairly straight forward

approach to the problem, no synthetic pesticides of any kind are permitted to be

used in any field or even livestock feed grains for any product which is to be

labeled “Organic”, at anytime during production or in the three years prior to

planting (3). This, however, leaves the organic

producer with a difficult task, how do they maintain economic levels of

production and loss without using synthetic pesticides? Natural pesticides such

as oil from the Neem tree are permitted but are not as entirely effective or economically

viable as repeated treatments of traditional pesticide.

The current solution is creating a

robust production system along side an integrated pest management system(IPM);

a system that encourages the crop to grow most vigorously while also employing

a pest management system that seeks to holistically control pests by

controlling all facets of their ability to thrive, not just kill them outright.

Various strategies are used, many of them ecological, such as: controlling the

pests environment, interrupting the pest’s life cycles, removing plants which

are already infested, using traps or even “trap crops”(crops which have no

market value but serve to distract pests), or, most interesting to me, using

beneficial predatory insects to control pest populations. To the outsider this

seems illogical, weren’t bugs the problem? But, by promoting a more natural

beneficial arthropod (insect) population, pest insects can be controlled to

economic levels.

The pollinators

are great, but save the Ladybugs!

The importance of natural

pollinators and the threat to their continued survival has not been understated

recently, at least in the ecological and agricultural communities, I cant speak

for the whole of America, but I know the “Save the Bees” campaign was quite

visible in this area. The effects of agricultural systems on the natural

ecosystem as a whole has been less visible to the layperson. The line between pollinator

and “we need food” is direct and obvious to most. I would say that the

importance of promoting a more naturally balanced arthropod community in an

effort to reduce explosions of pest populations is less intuitive. The next

campaign should be called “Save the ladybugs”, they’re cute like bees and are

also voracious predators (crazy right?).

Conventional agricultural systems are fairly

sterile from an ecological standpoint, there is the cash crop and the soil,

nothing else belongs there and is to be removed. Producers remove any biota

that may effect the crop (weeds and pests) and attempt to grow as much produce

as possible while using herbicides and pesticides to control any problems that

appear; environmentally conscious producers will employee minimal pesticides

but this is not always the rule. Conventional

producers fill a field with tasty treats for that crop’s pests and then control

any pest “Booms” with pesticides. The problems with this strategy are two

sided. On one hand, the pesticides are almost necessary at this point for

traditional producers to have economic returns, without them pests would devastate

most crops and pesticides are generally effective at stopping this,

disregarding acquired pesticide resistance. On the other side of the coin, these

pesticides are causing significant non-point pollution problems; they are

killing insects they aren’t intended too (4), are doing so outside of the area

where they are applied (4) and the entirety of these effects is not at all thoroughly

understood (4), like many topics ecological in nature.

When these pesticides are removed

from the equation in organic agricultural systems the first problem persists, pests

will devastate a crop where they are not controlled. How can they be

controlled? One of the most effective strategies is to promote beneficial arthropods

that will consume pests, by providing bio-diverse habitats that attract them

and promote their competitiveness (5).

But does it work?

In an agricultural setting, food

for pest insects is abundant and generally problems arise when there is no

balance in the natural system and these pest insects are not adequately

controlled by their natural predators. This problem could arise from a variety

of reasons. The predatory insects life cycle may be interrupted by agricultural

practices, the predatory insects may be separated spatially or temporally from

their prey, or the predatory insects are not adapted to the crop plant and do

not have suitable habitat. In recent years it has emerged that these non-crop

habitats are very important to the life cycle and competitiveness of these

beneficial “natural enemy” species (6). It has been shown that many types of

native “weeds” and selected species can be used at field margins, within fields

and even in the surrounding landscape to promote natural enemy species (5).

I have selected three studies which

demonstrate the effectiveness of increasing biodiversity on reducing pest

populations. The first is a study on intercropping polyculture fields of

vegetables with sunflower, that is, planting sunflowers adjacent to multiple vegetable

species in the same area. Jones Et al. found that sunflower plants were shown

to attract parasitoid insects almost immediately after establishment and

pollinators were attracted after flowering (7). The second trial in the study

found that sunflowers attracted these parasitoid insects and also had showed a

similar increase in the area (1m) around the sunflowers as well as higher levels

of pests on the sunflowers suggesting that they could function as both a

habitat for beneficial insects and as a trap for pests. The study also showed

that a huge variety of beneficial insects occurred on or near the sunflowers,

as shown in Table 1.

|

| Table 1: Occurance of beneficial insects in and around sunflower plots |

The second study I found related to

this topic examined the effects of managed hedgerows on field margins and

compared them to sites with weedy edges. Moradin et al. found that parasitoids

were more abundant in sites with hedgerows, that pest control was enhanced in

sites with hedgerows and that the benefits of these hedgerows extended up to

200m into the field. Most importantly to this study it was found that fewer of

the fields adjacent to hedgerows reached threshold levels of pests would require

pesticides.

The third study examined the use of

relay cropping cereal grains and other species (wheat, canola, sorghum) into cotton fields. This study by Parajulee et al. was interesting

to me because while it is not a market vegetable like I mentioned in the

beginning, cotton is notoriously plagued by pests and before Bt Cotton (pest resistant,

modified genetics) required extensive pesticide use. This is likely to become a

problem again in the future as pests acquire resistance to this new poisonous

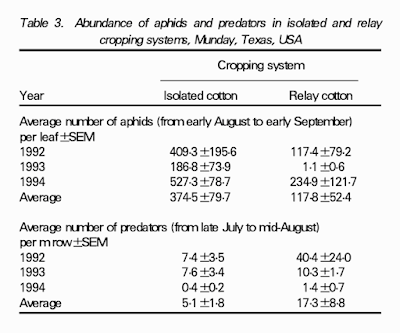

cotton. As shown in figures one and two cotton aphid populations were drastically decreased during the critical growing and harvest season, the occurance of aphids in the relay cropping systems decreased over-all and the occurance of predatory insects increased over-all.

These studies are not rare or isolated. Increasing biodiversity has been shown to have a significant beneficial effect on many different crop types over many years with several net positive benefits such as increased yields, decreased inputs and improved ecological health.

|

| Figure 1: Abundance of Cotton aphids in isolated fields and fields with selected relay crops |

|

| Figure 2: Abundance of aphids and predators in isolated and relay cropping systems |

Works Cited:

1: Crop losses to pests. Oerke, E. (2006). The Journal

of Agricultural Science, 144(1), 31-43. doi:10.1017/S0021859605005708

Polyxeni Nicolopoulou-Stamati,

Sotirios Maipas, Chrysanthi Kotampasi, Panagiotis Stamatis, Luc Hens. Front

Public Health. 2016; 4: 148. Published online 2016 Jul 18. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00148

3: United States Department of Agriculture; Guidelines for

Organic Crop Certification, https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Crop%20-%20Guidelines.pdf

4: The Effects of Microbial Pesticides on Non-target, Beneficial

Arthropods. J. Flexner, B. Lighthart, B.A. Croft. Agriculture, Ecosystems &

Environment, 16, 203-254, July 1986. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8809(86)90005-8

5: Landis, D., Menalled, F., Costamagna, A., &

Wilkinson, T. (2005). Manipulating plant resources to enhance beneficial

arthropods in agricultural landscapes. Weed Science, 53(6), 902-908.

doi:10.1614/WS-04-050R1.1

Douglas A. Landis Stephen D.

Wratten and Geoff M. Gurr. Annual Review of Entomology 2000 45:1, 175-201

7: Gregory A. Jones and Jennifer L. Gillett "INTERCROPPING WITH SUNFLOWERS

TO ATTRACT BENEFICIAL INSECTS IN ORGANIC AGRICULTURE," Florida

Entomologist 88(1), (1 March 2005).https://doi.org/10.1653/0015-4040(2005)088[0091:IWSTAB]2.0.CO;2

8: Morandin, L. Long, R. Kremen, C.(2014) Hedgerows

enhance beneficial insects on adjacent tomato fields in an intensive

agricultural landscape. Agriculture,

Ecosystems & Environment, 189, 154-170, May 2014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167880914001662

9: M. N. Parajulee , R. Montandon & J. E. Slosser

(1997) Relay intercropping to

enhance abundance of insect

predators of cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii Glover) in Texas cotton,

International Journal of Pest

Management, 43:3, 227-232, DOI:

10.1080/096708797228726

Comments

Post a Comment